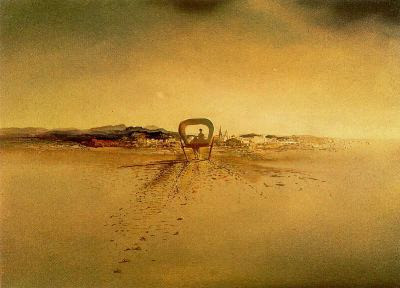

Cuando me incorporé tuve la sensación de haber sido animado por una corriente eléctrica. Mi esqueleto estaba intacto y podía mover los miembros sin dificultad, en el trágico paisaje. Sobre la estéril extensión nada acusaba a la vida. Todo lo que alguna vez fuera animado, todo lo que surgiera sobre la tierra por el raro soplo del germen, los edificios, los árboles, los hombres, las aguas, el ruido del mar, todo había concluido. Me encontraba sobre una yerma extensión despoblada. en el horizonte ilimitado y oscuro, nada se destaca sobre el suelo. El Sol, como un foco enorme y amarillo, estaba inmóvil en el vasto confín, y ya sus nubes inmóviles encapotaban el cielo. A mi derredor había un gran hacinamiento de huesos y era dificultoso ver el suelo. De pronto sentí una vibración uniforme que agitaba todos los despojos. Como movidos por una corriente el eléctrica intermitente, los huesos pugnaban por levantarse y volvían a caer sin movimiento como desmayados. El tinte pálido del Sol, ya muerto, animaba cloróticamente aquella doliente visión.

Entonces vínome a la memoria, después de grandes esfuerzos, el pasado. Me parecía haber despertado de un sueño rápido. Hice recuerdos y coordiné lo siguiente: Yo estaba la última vez en mi lecho. Una luz pálida iluminaba mi alcoba y un amigo, mi médico, teníame el pulso, grave, sin pronunciar una palabra. De pronto entraron en mi habitación mi madre y mis hermanas. Sentí un cuchichear de voces, vi caras entristecidas, y a una palabra del médico, rompieron a sollozar. El médico hizo una seña. Ya no podía moverme; había perdido el dominio sobre mí mismo y los párpados caían sobre mis ojos, pesadamente. Pero mi conciencia estaba perfectamente clara. Oía aún sollozos; sentí que alguien, mi madre, me abrazaba llorando; sentí que un Cristo de metal descansaba en mi pecho; una mano pasó frente a mis labios un espejo, y después todo se desvaneció.

Yo debí ser sepultado, naturalmente en el cementerio de mi pueblo. El cementerio no distaba un kilómetro de la ciudad; nosotros poseíamos un mausoleo. ¿Por qué, pues, me encontraba yo en este desolado paraje, cuando el espíritu volvía a animar mi esqueleto en esta hora definitiva?

Quién podía haber trasladado mis restos a este extraño lugar? Por otra parte, dónde estaban mis seres amados? Por qué me encontraba yo solo en medio de tantos despojos? Una duda mortal y fría me lastimaba. Extendí la vista para buscar en la extensión gris algo tangible a qué poderme referir y vi lejos, muy lejos, sobre la enorme extensión de huesos, un esqueleto que como yo, se elevaba en aquel campo de desolación. sobre la gran cantidad de huesos se incorporaban ya algunos esqueletos que trataban de ponerse en pie; pero volvían a caer sin ánimo sobre la tierra. Me encaminé con dificultad entre las óseas capas hacia el esqueleto. A mi paso cruzaban de repente, con velocidad tibias, omóplatos y cráneos que iban a reunirse con sus cuerpos. Llegué donde el esqueleto, solemne y grave, se erguía. Miraba cuando yo, acercándome, me puse a su lado.

-Quién sois, espíritu, y dónde estamos? - le dije.

No respondió.

-¿Qué ha sucedido? ¿Qué extraña pesadilla es ésta? ¿Por qué me encuentro aquí? ¿Vos no podrías responderme? ¿Quién ha animado mis huesos, quién me ha dado de nuevo estos sentidos que me permiten razonar? ¿Por qué mi cuerpo ha venido a aparecer aquí? ¿Qué tiempo hace, decidme, que desaparecí de la vida? ¿Dónde están mis seres amados? ¿Es esto la tierra? ¿Es aquel el Sol? Habladme, por vuestros más caros recuerdos, dadme una luz que amortigüe esta duda cruel... Estamos acaso en el infierno? ...

El esqueleto no me respondía.

-¡Decidme, por Dios, una palabra! ¿Qué tiempo hace que dejé de ser?... Yo era de una país joven, de un continente nuevo; cuando yo vivía, la vida era buena, los árboles alegraban el mundo, los ríos corrían desbordados, un soplo de actividad hacía evolucionar lo creado. ¿Dónde estamos?...

- En la tierra.

-¿Pero y el Tiempo?

-Ya no hay Tiempo.

-¿Y el Espacio?

-Ya no ha espacio.

-¿Y el sol?

-Véle allí, que agoniza; ya está inmóvil.

-¿Que ha pasado por el mundo?

-Los siglos.

-¿Estamos, pues, en el fin? Hemos sido llamados por Dios? ...

-¡Quién sabe!

-¿Vendrá ahora una manifestación divina, seremos destinados a otro planeta, a otra vida? ...

-¡Quién sabe!

-¿Han pasado muchos siglos? La humanidad ha vivido mucho tiempo? ¿Dónde está el progreso de los hombres? Nada ha quedado, acaso, de todos los esfuerzos, de todas las preocupaciones; ha podido el tiempo destruir tantas cosas magnificas?

-¡Quién sabe!

-¡Habladme, por Dios! Dadme una luz, sacadme de esta tortura o dejadme en la nada, pero no prolonguéis este estado de laceración. ¿Esta noche terminará? ¿Habrá una nueva aurora?

-¡Quién sabe!

En la extensión desolada y sombría, algunos esqueletos comenzaron a moverse y a animarse. Caminaban lejos de nosotros, en diversas direcciones.

-¿Vos sois acaso cristiano? ¿Conocisteis y amasteis a Cristo?

-Tú hablas de Cristo. ¿En tu tiempo aún se le conocía? ¿Eres tan viejo? Otras religiones se sucedieron en el mundo. Muchas vueltas dio la Humanidad. Hubo otros profetas, otros ideales, otras religiones, y tantas, que la Humanidad dudó un día que Cristo hubiera existido y que su religión hubiera tenido prosélitos.

-Eso es imposible. Cristo vive en el cielo. Cristo me salvará. Cristo está a la diestra de Dios, él era el Hijo de Dios, él velaba por la especie y por el Espíritu humano.

-¡Quién sabe!

-Cristo, a la hora final del Universo, vendrá a buscar a sus hijos, intercederá por ellos ante Dios, les dará una mansión de bienaventuranzas...

-¡Quién sabe!

-Allí nos reuniremos todos los que en vida nos amamos. Allí encontraremos todos los que en vida nos amamos. Allí encontraremos a nuestros seres queridos. Allí el espíritu de los buenos tendrá una dulce consolación.

-¡Quién sabe!

-Mi alma y mi cuerpo serán vueltos a la vida. Y mis amados serán vueltos a la vida y todo lo que fue volverá a ser.

-Tú no eres tú. Tú no fuiste. Tú no serás tú. Tu cuerpo venía de la tierra. Lo que fue un día en la vida tu sangre, había sido antes la vida latente de una serie de sustancias. Tu sangre vino del mineral que absorbe la planta y que dio el dulce fruto de nutrición a tu padre; en tu sangre había gases de la atmósfera que alimentaron los pulmones del que te engendró. En tu cerebro había neuronas que se componían de sustancias químicas y que se animaban al calor del sol, al efluvio de los cuerpos compuestos, al estímulo de excitantes diversos. Todo tú, eras sacado de la naturaleza. cuando volviste a la tierra, tus gases descompuestos ardieron en el fuego fatuo y se descompusieron en el aire; tus grasas alimentaron la tierra y dieron savia a los árboles del cementerio, de tu cerebro salieron gusanos, que dieron vida a las crisálidas, y un día las crisálidas levantaron sus finas alas en la limitada extensión del ataúd, en las sombras, y murieron, y también fueron nuevos gases que filtraron el zinc de tu caja. En tu cuerpo había aceites que penetraron en la madera y la pudrieron; en tus huesos había sales y sustancias que se descomponieron y se disgregaron y abonaron las raíces que los árboles buscaban. Un día nada quedó de tu cuerpo. Todo lo que formaba la armonía de tu ser, está hoy repartido. Una parte fue a convertirse en la madera de un mueble; otra parte, vegetal, fue a filtrarse en las neuronas de un hombre; los minerales sirvieron de componentes a una fortificación de guerra; algo de ti fue al espacio con otros elementos. Tú estás disgregado en la Naturaleza. Pero ya el sol no anima y la sustancia no vibra, y todo, todo, ha concluido definitivamente.

Ahora somos una vana imagen intangible; somos un recuerdo; pero toca tus miembros, busca tus huesos; no encontrarás nada, nada,

Y toqué mis miembros y nada era perceptible. Yo era una especie de efluvio, una idea, algo intangible, vago.

-Pero la humanidad no puede perecer así. Tenemos un fin. Yo soy creyente. Yo creo en Dios.

-Dios era lo que animaba el mundo y ya ves que no existe el mundo. Dónde está, pues, Dios?

-Dios existe y es eterno. El vendrá por sus hijos. Jesucristo me acompaña. Yo creo que él vendrá; él es la esperanza, el áncora de salvación del mundo. El se sacrificó por los hombres...

-¡Quién sabe!

-El no puede abandonar a los suyos. Vamos a invocarle. Vamos en pos de él. Recemos. Recemos, por Dios, recemos; la oración nos acercará al Creador. Jesucristo oirá nuestras plegarias.

-El esqueleto quedó un gran momento silencioso, con la calavera inclinada sobre el esternón, en desoladora actitud.

Yo comencé a rezar, espantado, contrito, poseído por un pavor trágico: Señor mío Jesucristo, dios y Hombre verdadero, Creador del cielo y de tierra...

-No reces, es inútil.

-¡Madre mía, madre mía! ¿Dónde estás? ¿Por qué no oyes mis clamores? ¿Por qué abandonas a tu hijo? ¿Dónde están tu espíritu, tu amor inmenso, tu abnegación y tu martirio? ¡Madre mía, madre mía! -gritaba yo desconsolado y mi voz se perdía sin eco en la extensión siniestra.

-¡No llames, es inútil!

-¿Pero por qué esta tortura? ¿Por qué esta crueldad? ¿Por qué se me ha vuelto a la vida, por qué esta maldita razón? ...

-No protestes ¡Es inútil!

Entonces yo me arrodillé a los pies de aquel raro esqueleto, y le dije sollozando, con toda la sinceridad de mi alma:

-¿Escuchadme: vamos en pos de Cristo. Invoquemos a Cristo; él es el único que puede salvarnos; él no nos abandonará; recemos, señor, recemos; sed piadoso, sed creyente; tal vez por vuestra falta de fe, él no nos escucha. Aunemos nuestra plegaria; creed en Cristo...

Y él, con una tristeza infinita, con una desoladora melancolía, con un desencanto indescriptible, inclinó la apesadumbrada cabeza y me dijo estas palabras:

-Hermano mío, Cristo soy yo.

Los huesos se animaban, se animaban, y el sol iba oscureciéndose, fijo en el mismo punto del horizonte.

Abraham Valderomar (1888 - 1919)